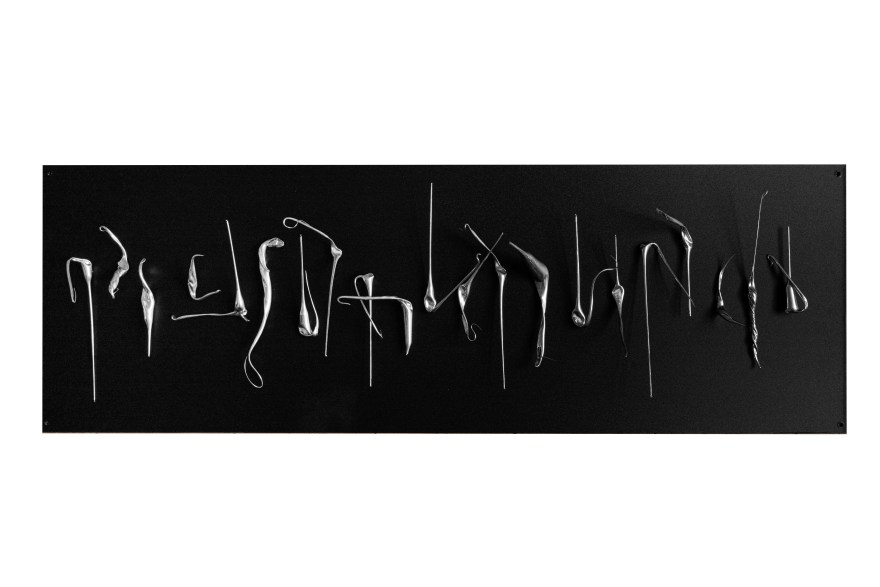

‘Remains’ (2024), Salvaged borosilicate glass from Wearside Glass Sculptures, chrome marker, and magnetic board. Part of ‘Lines, Threads and Traces’ curated by Ayako Tani for the International Festival of Glass (IFOG). Photos of ‘Remains’ by Rachel Deakin. Also remade for the exhibition was ‘Vibrant Matter’ (2016), Salvaged glass, acrylic paint, and pins, photo by Alex Crosby. Made possible thanks to NSCQ Bursary.

‘Remains’ is a continuation of the #recraftingwaste series of works, that I began in 2015 as part of my practice-based PhD at National Glass Centre, University of Sunderland. The glass is salvaged from Wearside Glass Sculptures, based at National Glass Centre, and they are likely to be waste from objects made by Brian Jones. Brian is a highly skilled scientific glass-blower or ‘lampworker’. These remnants will have been pulled off an extremely hot piece of borosilicate glass and thrown into a tray to cool. Interestingly in a sister piece ‘Vibrant Matter’ (2016), where I had painted the waste glass in fluorescent paint, Brain did not recognise this waste was from his bin, he assumed I had altered the glass in some way.

Each piece of glass is unique, and for me they possess different personalities. I have used a chrome marker to highlight the contours and bring attention to the movement frozen in time. The magnets allow for endless reconfiguration and different discussions to take place between the pieces. There is a playful and temporary element in the use of a magnetic board.

‘Remains’ refers to what is left after something is made and acknowledges that lampworking is a craft skill in decline and at risk of being lost in this country.

Tim Ingold gave a presentation at IFOG, about the ‘Lines, Threads and Traces’ show. He talked about my work ‘Remains’ and ‘Vibrant Matter’ compared to more monumental pieces of glass, using musical references. He kindly sent me this writing to explain his ideas:

“…I was comparing Webern’s music with the monumental symphonic works of composers like Beethoven and Brahms. These latter pulse with energy as they build up to their grand fortissimo finale. With Webern’s music, by contrast, the sounds are fragmentary, barely audible, never louder than pianissimo, playable forwards or backwards, and in no particular order. You can almost hear through them. As an example, I showed a slide of a page from the score from one of Webern’s ‘6 Bagatelles’ . For Webern, I think, every monument stands still and silent – that is to say, in a kind of inversion of the classical masters, it is silence that is monumental. The sounds we hear, by contrast, are like noises off – the door squeaking on its hinges, the crack of a cooling water pipe, a scampering mouse under the floorboards. It seemed to me that your glassy cast-offs were of the same order, and that there is also something unmistakably glassy about Webern’s music, as there is something musical about your piece. If it were notated, I’m sure it would look just like Webern’s score.” Tim Ingold, 2024