Helen Maurer + Helen Pailing + Graham Patterson

Including words by Katrina Porteous and collaborative works by Helen Maurer & Angela Moore

Between Work and Play is an exhibition that explores the tension between seemingly opposing states. Bringing together Helen Maurer, Helen Pailing and Graham Patterson in a lively exchange of light, shadow and transformed everyday materials, speak to creatures, the coastline and childhood memories. Driftwood, pins, glass and cast objects shape shift before your eyes, referencing the coastline’s dual relationship with industry and leisure. The artists share an experimental approach to making and retain a sense of playfulness often lost in adulthood. The works invite touch, spark curiosity and reveal new worlds in the simplest things, reminding us that reinvention is both playful yet urgent.

Several of the works in this exhibition were inspired or informed by poems from Katrina Porteous’s 2024 Bloodaxe collection, Rhizodont.

The Globe Gallery 22nd Jan – Sat 14th Feb 2026

Made possible thanks to funding by from North Shields Cultural Quarter

Images courtesy of The Globe Gallery, copyright Colin Davison.

Essay by Katrina Porteous:

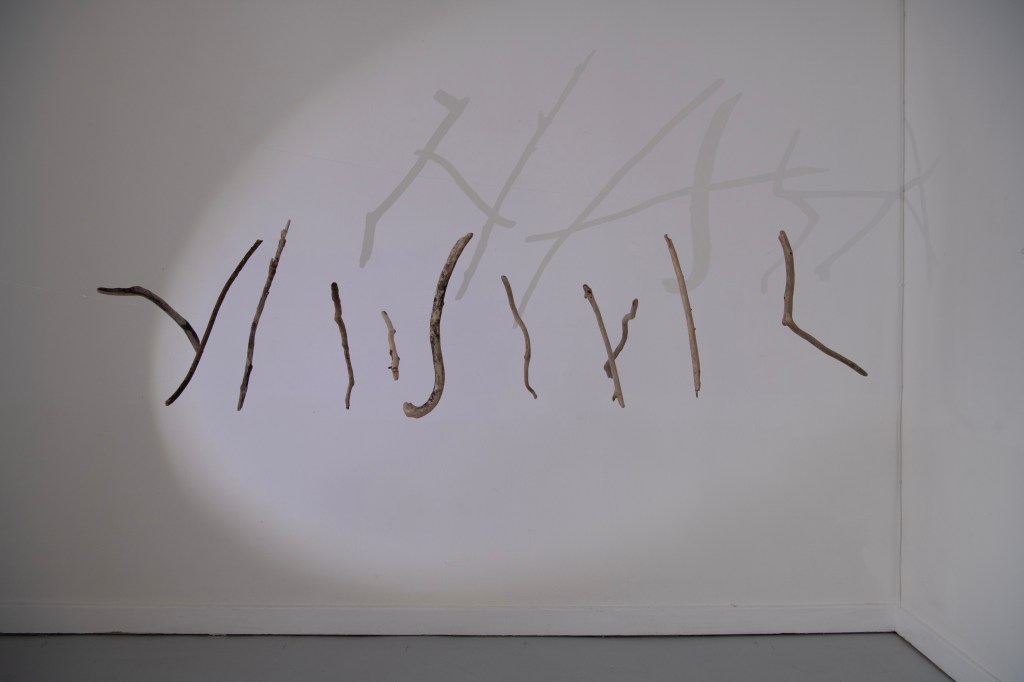

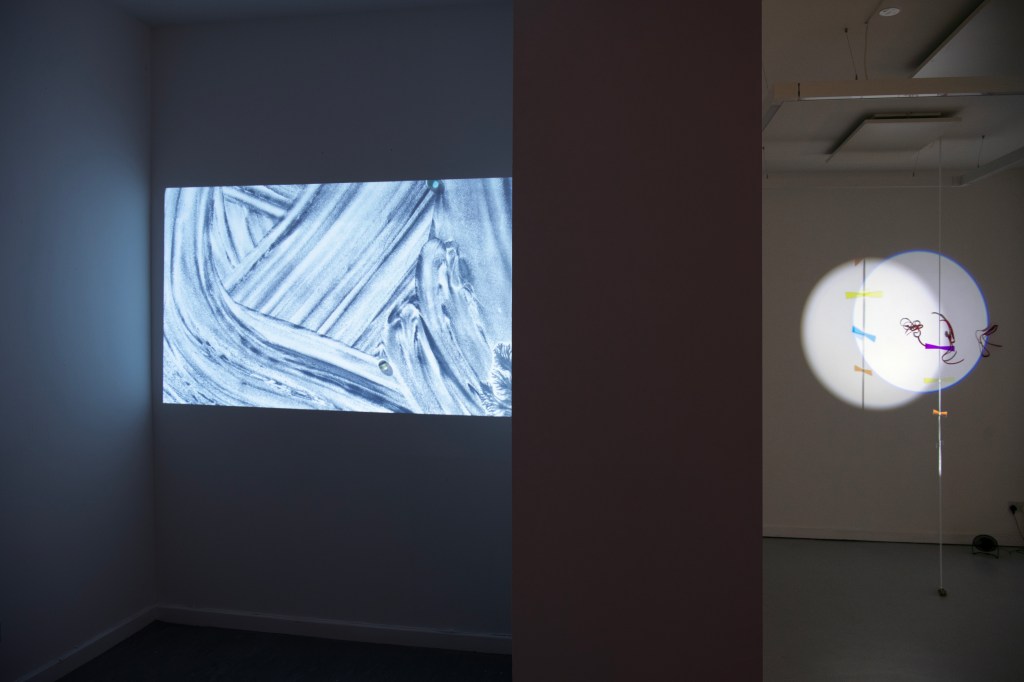

Blackened sticks, suspended in white space, dance to the vibrations of an eerie sound, casting ever-changing shadows. Thousands of pins, replicated in mechanical formation, shimmer like fish-skin or a fringe of chitinous bristles on a magnified sea-worm. The cast insides of kitchen spouts suggest caves, river-mouths, shells – mysterious sea-borne receptacles, expectant with possibility. These works by three quite different artists, Graham Patterson, Helen Pailing and Helen Maurer, gathered here, rhyme with one another unexpectedly. I, a poet – by definition a connector – have been invited to write this introduction, and to reflect on the artists’ work, while providing words which might inform parts of the exhibition.

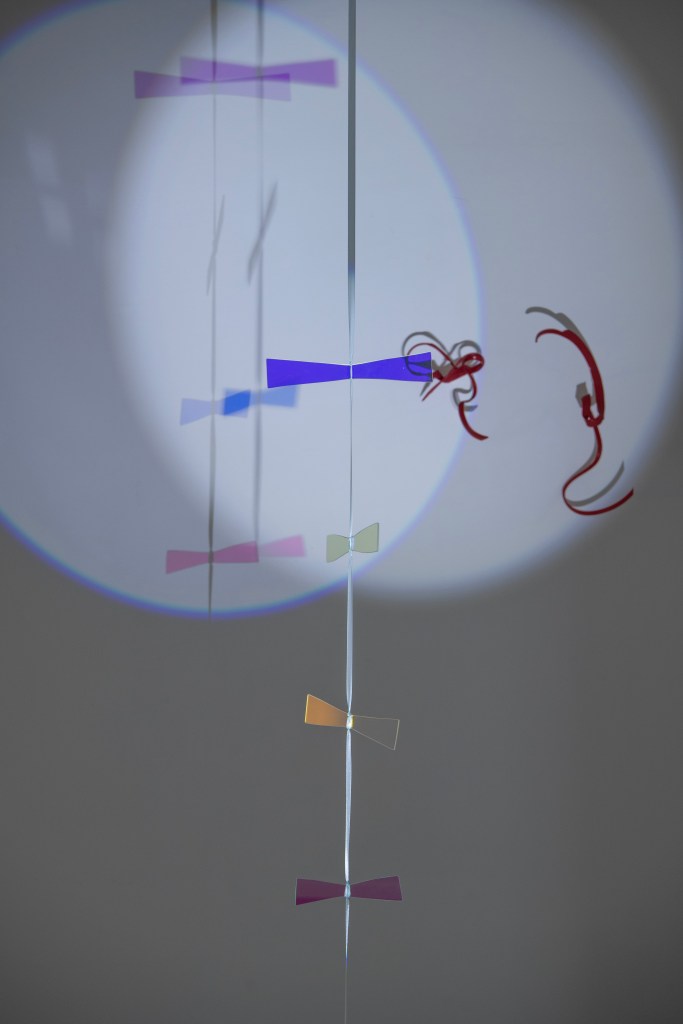

All three artists share a love of water, light and reflection. Patterson and Pailing both live close to the North Sea; Maurer was born in Portsmouth and lived for many years on a canal. All three are fascinated by simplicity, and draw on everyday materials in their work. Patterson gathers driftwood and discarded objects from the tideline, presenting them in sparse arrangements which reference both the industrial background of the sea and the respect for space and position found in ‘Ikebana’, the Japanese art of flower arrangement. His compositions bring out the dignity of working objects. Pailing, too, repurposes waste from the processes of making, whether fabric or vinyl, glass or household items such as bedsprings and window blinds, which she connects and transforms, using craft techniques such as stitching, wrapping and weaving, to create new work. Maurer endeavours to find a poetic narrative in relationships between objects at different scales, shining light through glass, filming through lenses, projecting onto a beach or a flexible screen. In my work, too, I explore scale and perspective, and often draw on collage techniques, assembling the bric-a-brac of found speech and sense observations from the North Sea beaches where I walk and fill endless notebooks.

Play is the key to all these works, and childhood objects are often the inspiration. For Pailing, a Slinky toy suggests an electromagnetic coil, a child’s Spirograph drawing a bedspring. The pin, which takes on a meditative quality when multiplied a thousand-fold, was once bent by a child to form a fish-hook. Maurer’s glass pebbles, used as marbles by children, create their own internal landscapes, seen differently from many angles. Where she has incorporated fragments of my text in these pebbles, and in glass powder, the words contract into bubble writing or break down into their smallest parts, potentially becoming something else entirely – perhaps something tactile, like Braille. ‘I thought if fish could speak,’ she writes playfully, ‘perhaps that might be how their hand writing might look.’

In each case, these are objects in transition. Metamorphosis is taking place, in what they are, how they are perceived, and what they mean. When Patterson appears to balance a fishing float or a child’s ball on the sea’s horizon, it is at once discarded plastic from the tideline, the moon which pulls that tide, and our entire planet, precariously positioned in time and space.

There is poetry in the way these objects resonate with one another. Human inventions echo nature’s own shapes and forms – an endless inventiveness which proceeds from universal principles, and which is referenced in this work in the sea’s waves, and in the oscillations of sound and light. Everything here is about relationship and interaction: meetings of unlike objects, of outside and inside, of object and viewer. Many of these pieces invite active involvement – touch or movement. The sensory, tactile qualities of each of these artists’ work stand in opposition to present day screen-based activities.

From the conversation between the three artists’ work, new ideas emerge. There is a juxtaposition of worlds, old and new. Patterson’s animated sticks and reclaimed objects are bare bones creating new life forms in shadow. Pailing’s vinyl offcuts become at once primitive squirming creatures, and a kind of calligraphy. In her hands old bedsprings, draped gracefully, transform into a discarded fishing net, and become in turn a sea creature’s tentacles. A scrap of frayed nylon rope, suspended, becomes a delicate prehistoric sea-slug. Within a discarded seashell trinket case, Maurer’s glass water-word beads become secrets whispered into ears. In reanimating abandoned objects, all three artists are preoccupied by anthropogenic effects on our environment. Pailing coats wire in graphite, its matt black referencing the carbon upon which organic life depends and from which fossil fuels derive.

My own work, too, investigates these themes in deep time, exploring the role that oceans play in the evolution of life, in erosion and deposition, and in the carbon cycle, as they absorb excess energy and regulate climate, acting as a ‘carbon sink’. Contemplating Helen Maurer’s cast spouts, which may be unborn foetuses, or perhaps ears, hollow and listening – strange ossicles from creatures long-extinct or yet to evolve – I’m reminded that the bones in our own ears are the remnants of our fishy ancestors from hundreds of millions of years ago. Maurer’s glass pebbles leave marks in sand like worm trails, flow over the reflected image of a great mountain that will one day be eroded to sand, and point to hypothetical future life forms, in a silicon-based world from which we have departed.

The exhibition presents us with uncertainty. What are we looking at? Work or play? Rescuing and repurposing material deemed ‘waste’ is, for all three artists, essential work – vital to our species’ very survival. But here, too, is endless, energetic wonder – in the dance of light and shadow on a beach, reflection, repetition and juxtaposition – a life-giving, childlike joy in the essential human acts of creativity and reinvention.